Shankar Borua is an independent filmmaker from Assam who has continued making cinema with a distinct sensibility and incorporates the voices of the many communities that make up the State.

Even though you never went to film school, what inspired you to pursue this line of writing as well as directing indie films?

My initial foray into the world of motion pictures began, I believe, when I was a little boy growing up in my hometown Duliajan in Upper Assam. My father, active with the Duliajan Film Society, back in the seventies, would have us kids watch wildlife movies playing off a 16mm projector at home. The cans, the screen, and the projector would occasionally be parked at our residence; that, I believe, was my first real encounter with motion pictures from close quarters, literally, because the screen would be put up in the living room just a few feet away from us kids sitting on the floor mesmerized by those moving images of African wildlife.

Today, I write and direct movies primarily because I find the process truly cathartic. As I make an effort to craft and tell a story, I always hope it will in some little way depict the human condition. I am in the business of meaningcreation and my job as a filmmaker is to create meaning through moving images. Film is an industrial art, humans and machines come together to recreate slices of life. This is true across cultures and continents and I am truly fascinated by this man-machine collaboration. I feel good to be a part of this story-telling caravan, my movies from this little corner of the world being a part of this vast continuum of work through a ‘modern’ art that will be enjoyed and evaluated by posterity. This is what really inspires me to write and direct movies.

Being based in Canada, why is it that you find yourself back in Assam making films?

Close to a little over a decade and half back, I migrated to Canada; from there I moved to the United States for higher education, a Masters and a Ph.D. I no longer live in Canada or for that matter in North America. I owe a lot to the continent though and will be grateful for my sojourn there which lasted for more than a decade. I am back in Assam to tell stories about our land and our people, stories that are authentic and portray not just the good but also the bad and the ugly. Hopefully, I will leave a body of work that will resonate long after I am gone. That is what I aspire for as I engage in meaning-making through motion pictures.

Your film, The Curiosity Shop, from the name to the story idea, followed an inspiration from Charles Dickens. Are you a big fan of Dickens?

I would say ‘who doesn’t like Dickens?’ A master storyteller, Dickens portrayed a dark world and often with fairly grotesque ends to his narratives. A lot of life is that, truly dark and fairly abhorrent under the veneer of civility and sophistication. Honestly, I am not well-read at all. I like to see and hear and write movies based on my own experiences and encounters, very little from imagination actually. However, Dickens and also Joseph Conrad, these writers always alert me when I am crafting a movie narrative; I am grateful to them as I make an effort to portray who we really are in my own little way.

You have been called "the rebel filmmaker" of the Assamese film industry. What do you think makes you a rebel?

A rebel with a cause, I would say, is a good thing for democracy to survive and flourish; dissent is what makes a mature community. As we humans got together to form groups and live as communities thousands of years back, true, we were bound by allegiances of different hues but also by a desire for individual self-expression within the group. A leadership that ignores that desire does it at its own peril.

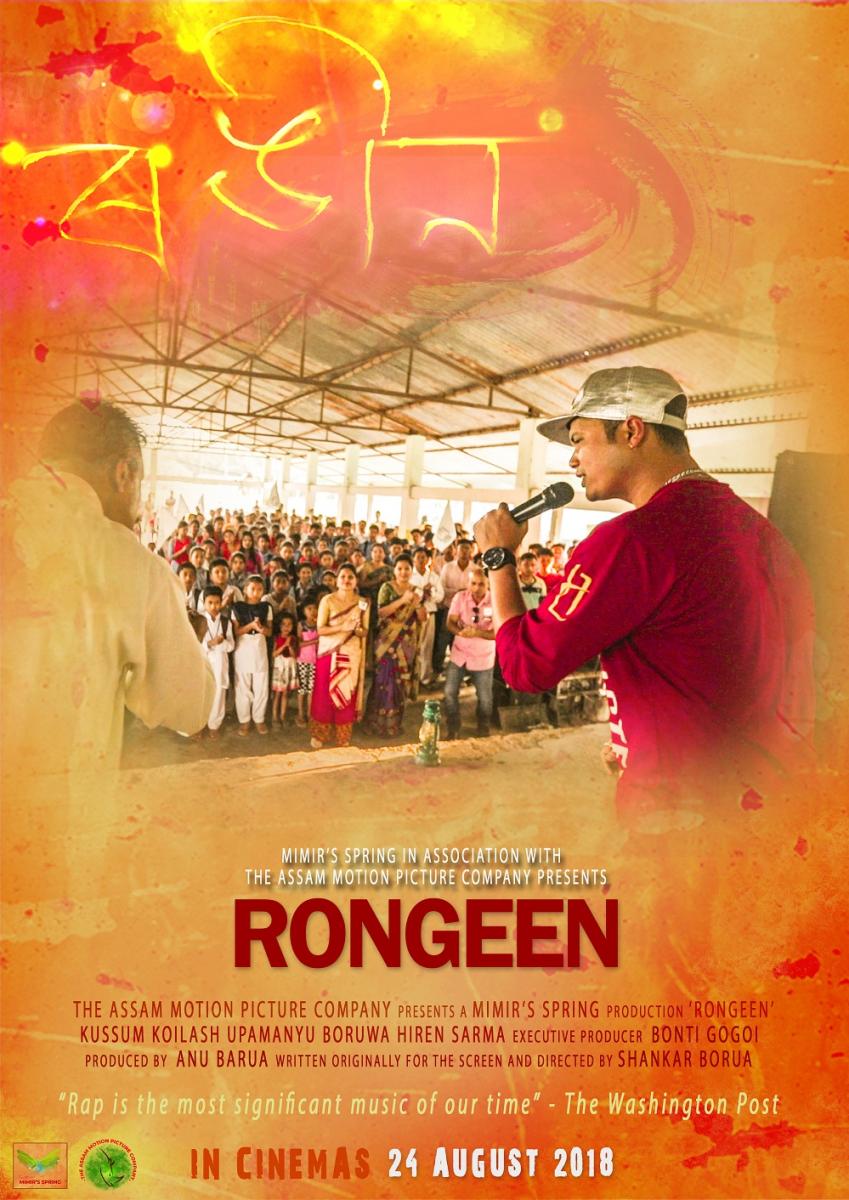

RONGEEN, my new movie, a musical, depicts rap music used as a political tool to highlight injustices around us here in Assam, to shine a light on a festering state of affairs. Rap, emanating from the inner-cities of urban America, is protest music that talks about racism, about police brutality, about rampant injustice. As rapper Kendrick Lamar was awarded the Pulitzer Prize (2017), The Washington Post called rap “the most significant music of our time.”

In terms of being a ‘rebel’ in the movie-making business, it makes perfect sense for me to craft out-of-the-box narratives that will not just provoke but also inspire alternative points of view. It makes a lot of business sense as well, offer something really truly unique and you have a winner at the box office. In a way, I truly am a ‘rebel filmmaker’ and I wear it on my sleeve proudly as a badge of honour.

Would you say you and your work is vastly different from those of the other filmmakers of the region?

All art is an extension of who we are as individuals. As I craft movies, it is only natural that I bring my own unique sensibilities to the narrative. My own inimitable style, if I do have one, also emerges from my choice of lenses and the way I move the camera to allow the audience to walk into the movie. It is like holding somebody’s hand and telling them ‘for the next two hours I am going to take you some place and you are going to like it, come with me for the ride.’

If the audience considers my movies as unusual and different, it is a direct outcome of the way I was raised, of the milieu where I grew up, the fault lines in our social formation that I encountered in my formative years (primarily of class and caste), my own little joys going on fishing and hunting trips with my father, and my deep sorrows when I have disappointed my mother. All of this builds into what I write as screenplays. What I attempt to show on screen is actually a lot of what I have personally undergone, at home and in the world outside, and how I have coped with and processed those experiences.

Over the years, I continue to learn how to make movies by actually making them, deliberately putting together sounds and pictures to the best of my ability and by developing a personal vocabulary and idiom that will take me forward in this very interesting but rather arduous journey of mine as an independent filmmaker striving to get his voice heard. I have definitely faltered at times, but I keep at it in the hope that I will touch someone deep inside in a way that they have never experienced it before.

Folks welcome narratives that are sincere and from the heart, pretence will only take you so far. An audience, primarily in Assam, is whom I make movies for. I only want to be judged by them. Did I touch hearts? Or as a storyteller did I come across as a phony and a charlatan? That is all that matters to me.

What are your thoughts about the independent filmmaking scenario in Assam? Does it have enough recognition and/or support?

Independent filmmaking and what I am referring to here is the work of auteurs, (folks like me who write and direct) is in an interesting place and time. With low-cost digital technologies available, this is truly a time where we should be producing movies relentlessly. Recognition and support will come, and I truly believe that. However, let the auteurs get a body of work out there first that is rooted in this region and stands out by being distinctly indigenous both in form and content.

We got to make movies for an audience here in Assam, not just for the consumption of an elite few some place else at a film festival. We got to take our narratives to our people in the interiors of Assam. Now, how do we do that? Sure, we need way more movie theaters. More importantly though, let us all get more imaginative and craft narratives that are sensible but also interesting and intriguing at the same time; trust me, it need not always be nonsense for it to be ‘interesting’.

Beginning the summer of 2015, I made three movies. RONGEEN is my third movie in three years after Grief on a Sunday Morning and The Curiosity Shop. This has broken my back, but, hopefully, I will keep at it and one fine day I will have an audience waiting for my next movie, which would be most gratifying.

What do you have to say about your acting career? Is it something that naturally came to you and pursued along with directing films?

In my acting career, I go by my screen name Upamanyu Boruwa. I was glad to start my career playing Xuntu opposite the legendary Biju Phukan in Grief on a Sunday Morning, a narrative about a dysfunctional father-son relationship with a very dark subtext, the sexual abuse of little boys. As I was writing the movie, I decided to seriously give acting a shot and went ahead. I am glad I made the move.

Then came The Curiosity Shop and I comfortably stepped into Rontu Bezboruah’s character, a naïve bookseller with an adopted daughter Hope (played by Debasmita Borgohain) learning the lesson of his life. In Rongeen, I play Domboru Borbora, the manager to the rap star Pobitro Sonowal (played by rapper Kussum Koilash) taking on the cunning and devious Puna Saikia (Hiren Sarma). All the three characters that I play are as different from one another as they can possibly be, so are the movies.

I am a non-actor in all senses of the term, never went to acting school, but I feel movie acting does come naturally to me primarily because I love getting under the skin of a character. The real challenge though is to maintain one’s creative edge in the midst of tedium. Acting in motion pictures requires repetitive performance in a very short span of time, doing the same thing over and over again till we get it right. Each time I act in a movie, it also teaches me a thing or two about directing. Folks whose work I have closely watched and continue to learn from as I began an acting career include, among others, Paul Newman, Tom Hanks, Morgan Freeman, and Gene Hackman.

How did you feel when your film Grief on a Sunday Morning won the Golden Camera award at the 1st Guwahati International Film Festival?

I was gratified that my craft was being recognized, also deeply humbled that a small independent movie made with the kind help of family and friends, primarily my mother and father, came thus far. I was also very happy for Biju Phukan and in my acceptance speech dedicated the award to him. Like they say, you are only as good as your co-star; I was lucky to have such a fine actor like him as my co-star. I directed him in my first feature Hepaah (All those longings…) but it was a rare opportunity to act alongside him in Grief on a Sunday Morning.

Your films are known for portraying sensitive characters and their relationships with each other (Grief on a Sunday Morning, The Curiosity Shop). How do you come about writing such intricate, unconventional storylines, and what inspires you to write them?

It is true that I am attracted to unusual stories and storytelling techniques and my screenplays reflect that. I etch characters that are deeply flawed, just like I am. Grief on a Sunday Morning unfolds linearly over 18 hours while The Curiosity Shop is a non-linear narrative moving back and forth across three timelines over several months. Human relationships and more often than not their associated tribulations lie at the core of my storytelling.

My writing is propelled by my need to understand and explore the human condition in all its hues; most of it is definitely not pretty, our frailties, our deviousness, above all our conceit and what we bring upon ourselves. As a craftsman, I am devoted to crafting tales that reflect our lives and the times in which we live. I hope my storytelling remains true to that purpose.

Your upcoming film called RONGEEN is set to release on the 24th of August, 2018. What kind of a story are you going to move the audience with this time?

RONGEEN (Colourful) is a political musical, a compelling and uplifting narrative, a classic David versus Goliath story set in rural Upper Assam where a small guy takes on a big guy in an electoral battle to settle an old score. A simple tale of good triumphing over evil, of truth triumphing over falsehood, RONGEEN, I hope, will be remembered by the audience for the enthralling songs and for our humble effort to highlight a region in South Asia not on too many a mind.

What does the title mean, in connection with the story?

The title RONGEEN tells us how colourful life is and can be, in spite of all that happens to us; the catch though is to find true colours in all that one does, from a mundane activity to building a community and a nation.

It is said that RONGEEN is a musical. Why did you choose to make it so?

RONGEEN is a musical with eight songs and I ventured to craft it that way to reach out to a wider audience across the length and breadth of Assam. Music is a fantastic vehicle not just to deliver a message overtly but also to showcase the beauty and splendour of this beautiful land Assam.

In RONGEEN people will get to see the magnificence of the beautiful river Dihing. In a way, the river is also a character in the movie singing a song, a witness to all that is happening around it. It signifies the continuity of life across generations and the triumph of good over evil. It was quite an opportunity to make a musical with the river Dihing as the central metaphor of the narrative.

Was shooting a musical a different experience than shooting any other film?

Of course, it was a whole another cinematic treatment that I was experimenting with, an enmeshing of politics and music in a two-hour narrative set in the interiors of Upper Assam. It was a challenge for me to weave eight songs within the narrative; I had never done a musical before.

What do you want people to take back after watching RONGEEN?

Life, indeed, is colourful if we choose to make it so; the brightest colour though comes from courage, the moral courage to stand up and be counted, to tell right from wrong, and to do the right thing. That is what I want folks to take back home after watching RONGEEN.

What can you tell us about your plans for the future?

In January 2019, we are hoping to begin principal photography for Wail of the Sun (Xouaa Saa, Beli Maar Gol), a dystopian narrative set in contemporary urban Guwahati centering round abnormal greed and anomie (normlessness). Hopefully, we will get to make A Mighty Wish (Mohot Aaxa ) in 2020 and then a few more movies. (Interview courtesy : Nandana Phatowali)

- 11359 reads

Add new comment