Without a geographical foundation, history lapses into deep confusion and obscurity; thus, facts begin to be cloaked in mythical terms. The Brahmaputra and Teesta Valleys have long been the targets of various waves of migration via the Tibetan Himalayas and the Patkoi Ranges. The migration from the valley of the Ruili, or Nam Mao of the Shans, during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries AD, followed the route connecting Pang Sau through the Hukawng Valley. Other ‘swarms’ following this movement went on to establish Siam (Thailand) and shape Arakanese society.

The migrations of Tibeto-Burman communities, including that of the Rabhas, into the Brahmaputra and Teesta Valleys have not yet been examined in detail through the lenses of geography — physical, human, sociological, and geopolitical — that prevailed at that time.

The trade routes from Tibet, through Bhutan, Monyul, and Sikkim, offered geographical connectivity, trading and travel passages, and helped in the spread of Buddhism as well as socio-cultural exchange.

Migrations of human communities from one landscape to another, whether radically different or similar, raise many questions that require explanation from a geographical standpoint.

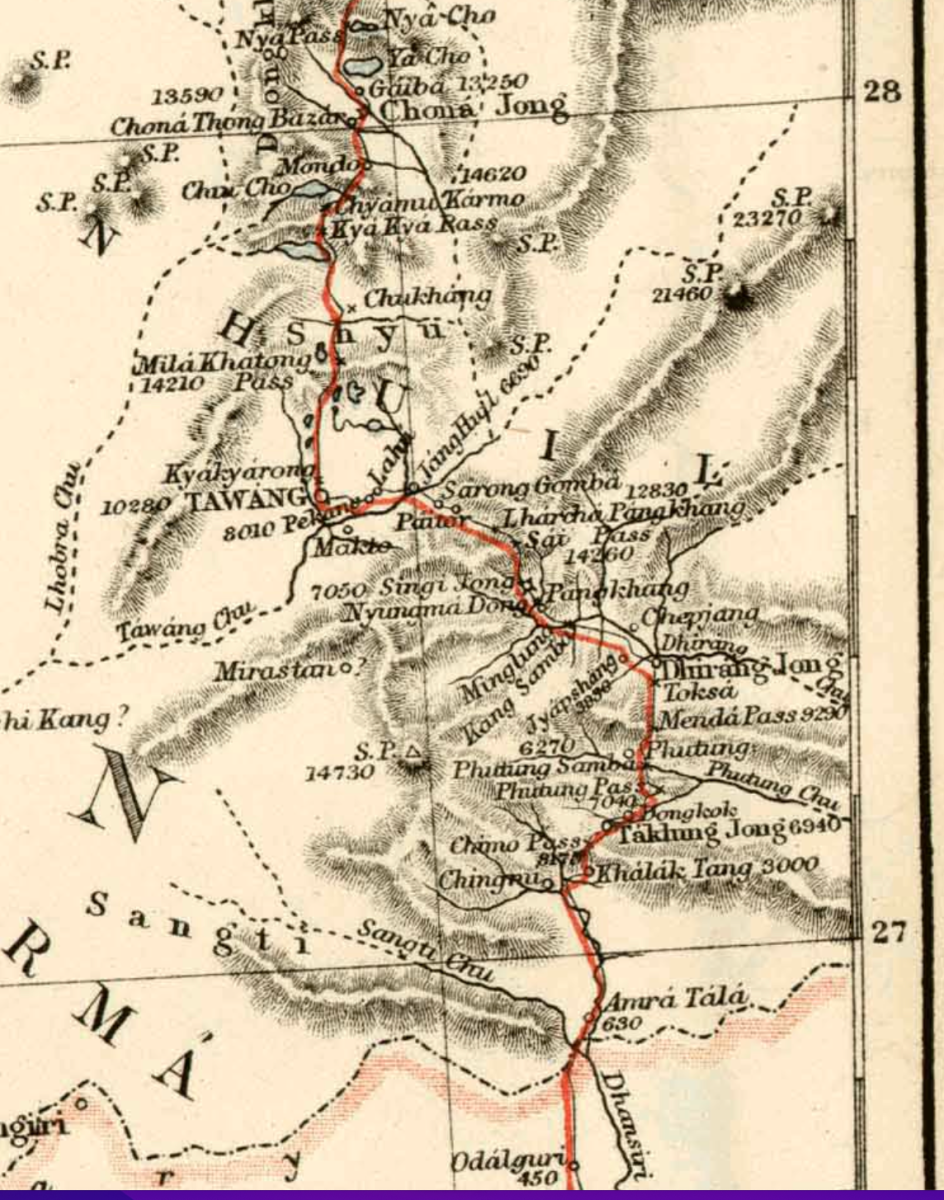

Fortunately for this study, certain geographical connections can be established. The starting point, from southern Tibet to the north bank of the Brahmaputra — where a prosperous civilization once thrived — could be located, and the routes are presented here through maps.

The Background Considerations

The outward migrations, with their push and pull factors, temporal setup, routes, and motivations of the ethnic groups involved, must be explained through historical investigation in a convincing manner. Resources alone need not be the only causative factors. The Brahmaputra Valley, without doubt, nurtured a civilization, though it has not always been the central focus of mainstream Indian historians.

Before the arrival of the Shans — who were later known as the Ahoms in the Brahmaputra Valley — several distinct communities had already adapted to and inhabited the region. Mention may be made of the Dimasas, a community belonging to the Tibeto-Burman group, whose capital was geographically located at Dimapur. They occupied a large geographical area, their territory extending on the western side of the Di-Khow River northwards to the banks of the Brahmaputra. The southern limit appears to have been the hilly terrain, which was a haven for various Naga communities. Other contemporary groups included the Chutiya and the Barahi in the upper Assam tract.

The names of certain rivers, such as the Dehing, Debang, and Disoi, suggest the north-easterly spread of the Dimasa civilization up to the foothills of present-day Arunachal Pradesh. The prefix “Di”, unambiguously meaning water or river in the Dimasa language, reflects this connection. The Dimasas probably had their own alphabet, as suggested by inscriptions found at the Badarpur Gate near the Barak River. Likewise, the prefix “Nam” has a distinct Shan/Tai influence, also meaning water or river, as seen in names such as Nampong, Namsai, and Nam Dapha.

As the Ahom kingdom consolidated its position and expanded westwards during the reign of Swargadeo Suhungmung, the Dimasas gradually lost their territory. By the 1600s, they had been displaced internally to the North Cachar Hills — to the valleys of Maibang and Mahur. The kingdom remained there until its eventual dissolution. This demonstrates how continual shifting, driven by political pressure, influences patterns of displacement.

It is difficult to determine the precise beginnings of the Dimasa civilization in the Dhansiri–Brahmaputra region. If they were inward migrants from an earlier time, their geographical position suggests the use of routes connecting to eastern Tibet. A major route through the Lohit Valley to eastern Tibet via Rima touched the commercial hub of Sadiya in the plains of Assam. Other routes connected upper and middle Burma (now Myanmar), eventually leading to Kunming in the Yunnan province of China.

Therefore, this area holds immense strategic importance for the inward migrations of many communities — the Shan (Ahom), Tai groups, Singphos, and the Lisu. The last of these, the Lisu, arrived around the 1930s in the Changlang area of the Namdapha Valley. The routes to Burma and China from this strategic location are listed below:

- From Sadiya through the Bisa Pass to the Hukawng Valley and the Mookong market on a navigable branch of the Irrawaddy River called the Nam-Yang. This was the Burmese invasion route to Assam in 1817.

- The route leading from Kibithoo along the River Dichu in the upper Lohit Valley to the Irrawaddy basin in northern Burma.

- Along the River Ghalum to Putao (Fort Hertz) in northern Burma.

- A path along the Lati River leading from the Lohit Valley to Burma.

- From Kambang Valley to Changkhari Dakhru, from where a route follows the courses of the Lam and Twang rivers.

- The most frequented route was the Chaukang path through the Chowkham Pass, used by traders from the Lohit and Dibang Valleys to reach Burma.

- Another route in the Burma segment, southeast of the Hukawng Valley, reached the Chinese district of Kakyo-Wainmo.

- Yet another important route connected the Dau Valley to the upper Lohit Valley along the River Tho Chu, from its source up to the neighbourhood of Kibithoo.

These routes fostered vibrant cross-border and cross-cultural trade and interaction. The Khamptis and the Singphos of the Lohit Valley traded in ivory, elephants, and opium. Though much of this trade operated through barter, the Chinese exchanged goods for bullion. The medicinal herb Coptis teeta (locally known as Mishmi teeta) and tiger skins were exchanged for gold dust by the Chulikata Mishmis of the Upper Dibang region with Tibetan merchants.

The purpose of listing these routes here is to identify the regions where various communities settled over long periods. The Dimasas, therefore, appear to have used these north-eastern routes through eastern Tibet. It is also quite possible that they utilized the trans-Patkai range routes through Burma. Such migrations would have required considerable time before a final settlement was reached.

Siu-Ka-Pha, the first Swargadeo of the Ahom Kingdom, is said to have taken more than thirty-five years to journey from the banks of Nam Mao in Moong Mao to his final resting place at Chorei Deo.

Trade Routes and the Migration of the Rabhas

Turning now to the Rabha community — once known for its matrilineal societal structure — an important geographical and cultural picture emerges. The locations of their early settlements in Darrang, Kamrup (north bank), and Jalpaiguri evoke intriguing historical insights.

Although an exact temporal coordinate cannot be established, we must turn to certain so-called mythological aspects. It is preferable, however, to view these not as myths but as alternative history. In this alternative historical narrative, the first settlements of the Rabha community were in the Darrang region, from which they migrated southward from hilly or mountainous areas.

During this time, there was bustling trade, commerce, and religious traffic flowing from southern Tibet via Tawang. The latter region was under the plenipotentiary authority of the Dalai Lama of Tibet. A journey of about a month would take a traveler from Lhasa, the Tibetan capital, to the thriving market of Tsona Dzong (rTso-na Dzong). From there, the route descended through Tawang, across the Se-La and Trashigang, eventually leading to Bhairabkunda via Amaratal.

Following the Anglo-Bhutan (Dooar) War of 1864–65, Major MacGregor surveyed this path. It took roughly a month to traverse the entire route (see Map ‘A’). This was the busiest and most popular corridor for travel and trade, through which even the influence of Tibetan Buddhism spread.

In the context above, the mountain passes (La in Tibetan) to the south of Tibet and the Duar (or Lhas Sgo) of Bhutan were key links. In this instance, the Duar involved was the Koriapar Duar. However, this Duar was under the rule of the Monpa. The word Monpa is a Tibetan omnibus term meaning “lowland people.” Their territory was known as Monyul, which served as an important strategic corridor — a fact still evident today in the geopolitical sensitivity of the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

Another crucial route, still in use, was the Yak-grazing trail employed by the Brok-pa graziers who traded in cheese at Bomdila. This was better known as Bailey’s Trail — the same alternative route used by the Chinese PLA to outmaneuver the Indian Army during the Sino-Indian War of 1962.

Map ‘A’ and the Dooars Region

The foothills of Bhutan — forming an approximately rectangular area of over 10,000 square kilometres — once contained eighteen Dooars or Lhas Sgo (passes).

In pre-colonial times, eleven Dooars lay within Bengal and seven within the Ahom-held area. The Bengal Dooars were of great importance to Sikkim and Cooch Behar. Indeed, Kamrup, Cooch Behar, and Sikkim were ancient trade partners, maintaining long-standing Tibetan export-import relationships.

This pathway, passing through Bhutan, traversed several mountain trails, connecting various passes and Dooars. After crossing the Dokhla and the Chumbi Valley — or the passes of Nathu-La and Jelep-La — Tibetan caravans, mostly on horseback, ponies, mules, and yaks, would arrive at Gangtok by way of the old Lhasa Road and then proceed to Darjeeling or Kalimpong.

From Sikkim’s easily traversed passes leading into the Chumbi Valley, the comparatively low (15,200 ft) and gently graded approaches of the Nathula Pass gave direct access to central Tibet and the Lhasa region. This area thus occupied a commanding position on the historic Kalimpong–Lhasa trade route.

Alongside the famed Nathu-La (Gnatui) and Jelep-La passes, there were more than a dozen others — such as Lachen, Lachung, Cho-La, Donk-La, Yak-La, Thanka-La, and more — connecting Sikkim with Tibet. Upon descending from these high passes, travellers would soon reach the plains of Cooch Behar through the Dooars of Dalimkote, Chamurchi, and others.

The Tashigang–Lhasa route mainly served Assam-bound traders, whereas the Paro–Lhasa route carried Tibetan trade destined for Bengal.

This route may well have been utilized by a separate wave of Rabha migration from southern Tibet — possibly from the territories inhabited by the fierce Kham-Pa warrior community. This could explain why certain sub-groups of the Rabha people today lack awareness of the alternative historical accounts of King Dodan and his followers.

The Internal Displacement of the Rabhas from Darrang–Kamrup

The exact period during which the Rabhas settled via the Dewangiri and Doimara–Bhairabkunda routes — linking southern Tibet with Darrang and nearby Kamrup on the north bank of the Brahmaputra (Bullungbhuttur) — is difficult to determine. The Hajo route is believed to have opened around the 7th century AD; hence, it is plausible that the users of this route, including early Rabha migrants, travelled during or after that period.

In the folklore concerning King Banasura and his son or general, Dodan, we encounter a timeline that overlaps myth and early history. If Banasura indeed lived during the mythical war between Krishna and Mahadeva, we must consider the period immediately following the Mahabharata war, when Krishna was said to be still alive.

According to astronomical calculations based on star positions by various authorities, the Mahabharata war has been dated to 3132 BCE (or 5157 years before the Common Era). Scholars such as Kak find this estimation convincing. Krishna is said to have lived thirty-five years after the war, and the Kali Yuga is believed to have begun thereafter. King Bhagadatta of Pragjyotishpur also fought and died for the Kauravas in that great war. Thus, Banasura appears to have been a close contemporary of the Mahabharata era.

However, it would not be proper to place King Dodan, the progenitor of the Rabhas, in so remote a time. The internal displacement from Darrang downstream along the Brahmaputra (Bullungbhuttur) probably occurred much later, under a different ruler who may have borne the same name.

This downstream evacuation — led by Dodan and his followers — likely resulted in the dispersal of the group into various regions. The quickest means of evacuation would have been the swift-flowing Brahmaputra River itself. Whether by rafts or boats, long columns of evacuees would have moved downstream, settling in scattered clusters.

Some groups likely established local governance around the Khetri–Dimoria areas, while the main body, following the river’s course, reached the mouth of the Jinjiram River and eventually settled in what is today known as Tikrikilla.

It is also worth considering the worship of the serpent goddess Manasa and the lore of Chando Sadagar, associated with South Kamrup near Chaygaon. Certain scholars claim that Beula — the central figure in the Manasa legend — may have belonged to the Rabha community. Such claims extend to regions in present-day West Bengal as well.

The South Kamrup sub-populations of the Rabhas are not easy to explain. Whether these areas once formed part of a contiguous socio-cultural landscape connecting South Goalpara along the valleys of the north-flowing rivers remains uncertain — though geographically, such continuity seems plausible.

The Rabhas and the Khasis together formed, along the nine Khasi–Kamrup Dooars, an integral part of a cross-cultural and cross-societal relationship. Chiefs (Syiem) of Nongkhlaw, Jirang, and Mawtamur appear to have ruled over significant stretches extending northward into the valley regions, illustrating the intertwined cultural geography of these communities.

Conclusion

This article briefly outlines the most plausible routes used by the ancient Rabha community during their migration in different waves toward two principal destinations — Darrang and the Teesta Valley. The maps included authenticate the traditional lore of migration passed down by the forefathers.

While the original sources of these movements remain difficult to specify or fully explain, the evidence presented here strengthens the understanding of the geographical and historical contexts in which such migrations took place.

A deeper appreciation of these routes may reshape our perception of the historical and cultural evolution of several communities in the Brahmaputra and Teesta valleys.

- 57840 reads

Add new comment